ABSTRACT

The problems, and benefits, are reviewed of using ’templates’ (standard lists of tasks identified for common asset categories) to assist in maintenance plan development. The reasons why problems occur are discussed, and a set of ‘Do’s and Don’ts’, to ensure that templating is employed in a positive, value-adding, way is proposed.

INTRODUCTION

Many organisations attempt to expedite the development of maintenance plans by using ‘Maintenance Templates’ as an out-of-the-box solution that specifies the maintenance to be performed on assets according to their category. This process is used on the basis that the use of templates will

- create a single source of truth so that all similar assets have consistency in tasks and task descriptions;

- make adjusting the strategy easier in the future, particularly if software is used, as only the templates need to be changed; these changes are then directly applied to all linked assets; and –

- result in a lower implementation cost, because time will not be wasted repeating analysis on similar assets.

Unfortunately, after a company embarks on this strategy they discover

- maintenance plan development time does not reduce, in some cases it even increases, because the developed plan is quickly observed to be excessive or inappropriate and not optimised, and ;needs to be reworked early in its life,

- no improvement in reliability is obtained, and availability often suffers due to an excessive number of tasks being developed, resulting in increased maintenance downtime; and

- excessive cost occurs due to unnecessary maintenance being applied to non-critical assets.

This paper reviews why these problems occur, and finishes with a set of Do’s and Don’ts to assist in ensuring that the use of templates occurs in a positive way that adds value to the process of maintenance plan development. This ensures that the business goals of lower cost, higher reliability, and higher availability are achieved rapidly from the maintenance plan.

THE USE OF TEMPLATING

The use of templates refers to the practice of having standard task lists identified for those common asset categories, such as a diesel engine, filter, pressure transmitter, gate valve, etc. that are applied to the asset hierarchy using software or spread sheet solutions. These templates are sometimes referred to as “maintenance strategies” or “failure mode libraries”. In theory, they allow maintenance plans to be developed by categorising the assets in a hierarchy and applying the relevant templates to them. This ensures a consistent maintenance strategy is applied to every similar asset in an organisation and the plan can be developed by less experienced and cheaper resources.

THE PROBLEM – WHY DOES THIS APPROACH GO WRONG?

The reasons for the failure of this approach can be tracked down to the following key issues.

1. The process fails to recognise a key concept of maintenance strategy development, viz. that maintenance is performed to maintain function. Organisations using templating often do not consider the function of the asset but only the category when developing maintenance plans; often this is driven by the functionality of the Computerised Maintenance Management System (CMMS).

Maintenance plans must be developed based on maintaining the function of the asset. The category of the asset assists in identifying a suite of possible preventive tasks that can be applied, not the effectiveness or cost benefit of applying those tasks.

2. Templates are often developed and applied prior to a high level maintenance strategy being finalised that includes the processes to be used in developing the maintenance plans.

The development of maintenance plans should be guided by a maintenance strategy supported by a set of standards and procedures. One of these documents might be a set of standard templates that can be applied to common asset types, such as instruments.

3. Templates are often applied using a bottom-up approach, starting at the lowest level of the asset hierarchy.

This approach can easily overlook the overall criticality or function of the system that they belong to. Prior to application of templates a top-down review of the system functions and criticality should be performed. This will allow evaluation, of the effectiveness and cost in maintaining function, of the template-listed tasks.

4. Often, the analyst applying the strategy is not trained in any Reliability Centred Maintenance (RCM) principles.

It is a flaw to think that because you have a template that it can be blindly applied to an asset. The analyst must have been trained formally, or through mentoring, to have an understanding of reliability principles and be conversant with the seven standard questions of RCM and, if dealing with a ‘brown field’ site, Preventive Maintenance Optimisation (PMO). This applies even where formal RCM is not being applied. The seven questions, as spelt out in SAE JA101,1 are:

a. What are the functions and associated desired standards of performance of the asset in its operating context (Functions)?

b. In what ways can it fail to fulfil its functions (Functional failures)?

c. What causes each functional failure (Failure modes)?

d. What happens when each failure occurs (Failure effects)?

e. In what way does each failure matter (Failure consequences)?

f. What should be done to predict or prevent each failure (Proactive tasks and task intervals)?

g. What should be done if a suitable proactive task cannot be found (Default actions)?

Where a PMO process if being undertaken then at least questions d to g should be asked, particularly ‘How does each failure matter?’

5. Hidden or secondary functions are often overlooked, resulting in critical function tests being missed. By definition, a critical function test is performed to ensure that a critical function is operative.

In high risk industries, to properly identify critical hidden functions maintenance plan development must consider asset function at both the system and physical asset level.

6. When applying templates people do not consider the effectiveness and applicability of the tasks.

When using templates the question “Is the task applicable and effective?” should always be asked. Often, tasks are chosen that are not applicable to the asset in question, due to technical differences such as greasing auto-greased bearings, or tasks are applied that will cost more than the consequences of a run to failure strategy .

(Note: This question should also apply to selection of OEM maintenance tasks. Many organisations, for example, insist on sticking to OEM recommendations in order to maintain warranty, or if the system is neither critical nor worthy of full RCM analysis. In both cases, the cost of maintenance must be less than the cost of repair or replacement of the asset to justify doing the OEM recommended task. If an OEM strategy is performed to maintain warranty then it should be reviewed once the warranty period has expired).

How should the organisation work with software tools and templates to improve its maintenance strategy? So far, we have focussed on some of the issues of templating; it can also have a number of benefits.

- Similar assets will have similar potential failure modes (as distinct from function). As such, templates are a good guide to what can fail on an asset and what can be done to predict or prevent failure. This can save time by not having to perform failure modes analysis from scratch.

- As similar failure modes exist for the same asset type, similar maintenance tasks are also likely to be applicable, templates will therefore have standard wordings for tasks. This can assist in ensuring consistency in wording of the selected maintenance tasks, and therefore the quality of the final work instructions. Too often, different maintenance analysts will develop a different wording every time they create a new task, even if a similar task already exists.

- They can be collated into a summary to provide pre-approval of possible tasks prior to too much time being spent applying them to the actual assets.

SUMMARY

Templating is a useful tool for assisting in the development of maintenance strategies but used improperly it can also be an enemy to achieving the business goals of cost control, reliability and availability. The following is a summary of the Do’s and Don’ts of templating:

DON’T –

Let software drive your maintenance plan development process. Use templates to automatically apply maintenance tasks and expect an efficient maintenance plan.

DO –

Develop a solid process to develop maintenance tasks for your assets founded on maintaining function.

Integrate your maintenance plan development process to the capability and functionality of any software solution that may have been purchased.

Ensure that personnel implementing a maintenance plan have at least introductory training to modern reliability principles.

Ensure that the use of templates is integral to the overall maintenance strategy for the plant.

Be sure, when applying a task, always to ask: “Is it effective and worth doing?”

Review your maintenance programme – if it is based upon an OEM requirement to maintain warranty – at the end of the warranty period.

EXAMPLE: A TALE OF TWO TEMPERATURE TRANSMITTERS

The following example concerns two temperature transmitters. For the purposes of the example we will assume that they are of the same type and manufacturer. They are located in a ‘green field’ plant currently being commissioned, and a group of maintenance analysts are developing maintenance plans. As part of this development a “Maintenance Template” document has been created that lists the standard tasks for a temperature transmitter as:

At one yearly intervals – visually inspect.

At four-yearly intervals – carry out three-point calibration and loop tests.

The functions of the parent systems and the temperature transmitters are as follows.

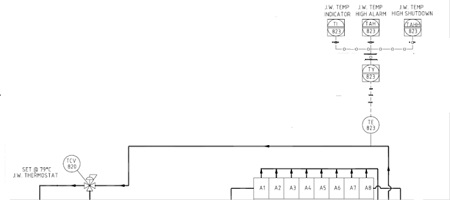

Case 1 (Figure 1)

The temperature transmitter (TE823) is located on an emergency black start generator (BSG) only used to provide power to start a series of gas turbine alternators. The BSG is only required in an emergency – about once per year when a blackout occurs due to other causes. The transmitter itself provides temperature information to an operator’s display as well as triggering a high temperature alarm, and/or BSG shutdown. A four-hour test run of the generators (failure finding task) is performed weekly to ensure that the units are operative. Temperature control in the diesel engine is controlled by a temperature control valve not linked to the temperature transmitter set to 79°C, and a check that the EDG is operating at this temperature is included in the test run check sheet.

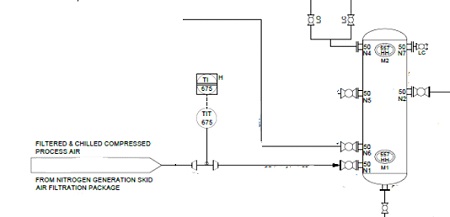

Case 2 (Figure 2)

The temperature transmitter (TIT675) is part of a nitrogen plant essential to the operation of a high capacity gas compression station. Failure to provide dry nitrogen will result in shutdown of the gas compressors and heavy financial losses. The plant will shut down if the temperature moves out of a target range and the transmitter’s function is to transmit the gas temperature to the control system.

A high level analysis of Case 1 shows that a functional failure of the temperature transmitter, or the temperature control valve, would be evident during test runs, as the temperature display would not read 79°C. If this is the case the technician should investigate whether it is a fault with the temperature transmitter, temperature control valve or other problem causing overheating. As such, there is no need to perform any formal calibration or inspection on this device because the failure of the transmitter is evident during weekly testing.

A high level analysis of Case 2 shows that a small drift of the temperature transmitter output could result in a false trip, because it may cause the temperature output to initiate an alarm even though there was no problem with the actual temperature. Such an output drift might lead to a plant shutdown, with high financial loss. In this case it is wise to perform regular calibration and inspection as per the template.

In summary, it can be seen that, despite these two assets being the same, it is important – if a suitable maintenance plan is to be developed – to understand the function and the effect of functional failure in each one’s operating context.