ABSTRACT

Those businesses which have achieved recognised levels of excellence across their enterprise do so by reviewing and measuring their organisation through quite different lenses from what might be considered by a “normal” organisation. Businesses that have achieved recognised levels of enterprise-wide excellence focus first on what they consider to be the ideal patterns of behaviour they need to observe at each level of the organisation. These behaviour patterns do not happen by accident. Instead they are supported, enabled and encouraged by carefully designed business systems which ensure the constant expression of this ideal behaviour. The role leaders play in supporting such an approach is critical.

In this article we review a way in which organisations can avoid reinventing the wheel when it comes to cultural change, and in particular developing a culture to ensure optimal equipment performance. We review and align the philosophy and principles behind the Shingo Enterprise Excellence Model and how it is completely compatible with the core thinking of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM).

This article is the second in a series of three. The first, Overall Equipment Effectiveness 1: The Three-Tier Model by Peter Willmott, appeared in Maintenance & Asset Management Journal, Nov/Dec 2019

Current state review

As the authors carry out initial reviews of businesses which are looking to embark on a change or improvement programme, we begin with a detailed current state review. In most cases we are not there because the business is performing exceptionally well (although this can be the case with regard to benchmark assessments); we are there because there is a clear reality that the organisation needs to significantly “up its game”.

The current state review involves a detailed walk-through of shop floor and back office activities, a review of overall performance, and one-on-one interviews with staff including the local site leadership team. It is the one-on-one interviews that provide the most information as to why the business may not be performing at its best, and help paint a picture of the true current state reality.

Where the business under review is reliant on the predictable and optimal performance of equipment, we find that issues with organisation culture and patterns of behaviour play a significant part in the absence of repeatable excellent performance of process and assets.

It is not surprising, then, that fewer than 10% of improvement programmes are truly successful and result in a lasting change to the base culture of the business. Those companies that achieve self-sustaining or “self-propelling” cultural change do so by focusing the business on ideal organisational culture and behaviour. Those organisations that are achieving sustainable excellence tackle culture and behaviour in a very particular way by asking a very searching question:

If we are to achieve a level of sustainable excellence in what we do, what are the ideal behaviour patterns we need to see expressed consistently within the various business functions and all levels of this organisation?

How do our current systems enable or disable this ideal behaviour?

This behavioural based approach is the foundation of the Shingo Enterprise Excellence philosophy, captured within the Shingo model and its associated ten guiding principles, as shown in Figure 1.

The Shingo Enterprise Excellence also puts forward three core insights:

- Ideal results require ideal behaviour

- Purpose and systems drive behaviour

- Principles inform ideal behaviour

TPM’s alignment with the Shingo model

If these insights are viewed from a Total Productive Maintenance viewpoint they can have a profound effect on the approach to asset optimisation. Taking each insight in turn the organisation can begin to align its thinking with the concept of ideal equipment-related behaviour and the processes that, viewed as a whole, combine into a complete system of asset maintenance and optimisation.

The Shingo Model and its guiding principles provide insights into what these ideal modes of behaviour might be. Principles such as focus on process, ensure quality at source, embrace scientific thinking, seek perfection and the other principles within the continuous improvement dimension can easily be linked to observable behaviour associated with the maintenance and improvement of equipment performance. Such observable behaviour might include watching a team develop and test ideas and gather data to either fix a problem (permanently) or improve the process.

The principal focus on process might come to mind while watching and listening to a team review and discuss a piece of standard work in detail to ensure that the procedure actually reflects and highlights the critical control or checking areas of the equipment during a precision changeover.

Effective TPM teamwork in practice

In an organisation that is achieving consistent levels of improvement in machine output and quality, the author would expect to observe ideal behaviour patterns in relation to how familiar the operators are with their equipment and process consciousness – in the sense of a new found understanding of how the equipment actually works and its relationship within the overall production process. The operator would be expected to be actively engaged in problem-solving activity and process improvement along with his or her maintenance and technical engineering colleagues, as part of the way we do things here.

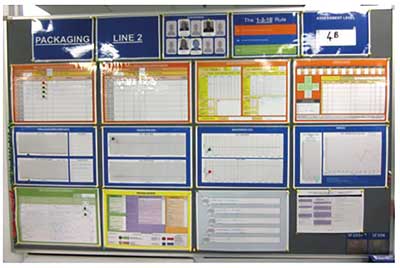

As illustrated in figures 2 and 3, highly user-friendly day-to-day visual management boards are sited at the place of work where leaders and managers have trusted the team leaders and their teams and progressively delegated responsibility for day-to-day running of the plant to them.

As an example based in the context of cultural enablers, the author would expect to observe mutually respectful conversations between operators and technical engineering groups who appreciate the value of the operator’s day-to-day experience of the equipment. Equipment maintainers and engineers would have a real and expressed appreciation for the value this knowledge brings to problem resolution, process improvement and hence improvements in maintenance and reliability.

Over time, as the process continued to stabilise and improve, the key questions in the weekly “look back” would increasingly be about what new insights on the process have the team come across this week that will drive innovation and improvement tomorrow, rather than what were the biggest issues this week. This focus on the relentless improvement on results and performance would align with the principle of customer value.

Now contrast the environment above with the patterns of behaviour that we commonly observe: operators read a procedure perhaps once, but they are shown how “to get the work done” by another “more experienced” operator. The relationship between the operator and maintenance technician is fraught and often tense. Both are overworked and stressed.

Typically, the maintenance technician is being pulled from pillar to post in a constant firefighting mode while trying to keep up with maintenance schedules and corrective actions to meet deadlines. The engineers responsible for the manufacturing line decide how the manufacturing process can be improved and introduce changes without any input or engagement from either the maintainers or operators. Measures used to monitor performance are not accurate (a fact known to the team), yet they are still asked to contribute to production cell meetings or improvement activities to improve the metrics.

Behaviour and systems thinking

If it is possible to distinguish between those patterns of behaviour that are ideal and those that are not, how do the systems in the business either encourage or discourage those ideal behaviour patterns? Do the systems have the potential to drive the wrong behaviour?

There can often be confusion over what is a system and what is a process and how these break down into tools and tasks. To keep it simple, the authors consider a system as the large end-to-end way core things are done in a business.

For example, think of a business’s people lifecycle management system. By this we mean a system that enables the right people to be hired, developed, performance-managed and retired. Such a system would be made up of many processes, such as how people are recruited, how they undergo their annual review, how they contribute to their personal development, and how they are trained. All can be regarded as separate but connected processes within an overall system. A tool within the hiring process might be the interview application form, the performance review mechanism, or the online training system, whereas a task might be how employees update their training matrix or contribute to their personal development plan.

A common example of a system driving bad behaviour can be observed (and measured) in many learning and development systems. One manifestation may be the situation whereby new employees are required to read, review, and sign off multiple procedures within too short a time. They may even be required to pass an online test of competence. Faced with an almost impossible task, the employee signs off procedures they have, at best, glanced at or, at worst, not read at all. But what about the online test? Many online tests are simply foiled by multiple attempts at answers until the right one is achieved.

What is the real or subliminal, behavioural lesson here: compliance is more important than knowledge? My signature has no real value? The key thing is to get the job done, no matter what it takes to get it done?

The author regularly sees maintenance teams driven to achieve maintenance task close-out rates for tasks that have no real value and should be eliminated. In carrying out these non-value-adding tasks, skilled maintenance teams waste valuable time that would be better used in investigating and eliminating problems or improving overall equipment performance. The focus is not only on solving problems but also on preventing recurrence of that problem with a permanent resolution or fix.

By viewing TPM as a core system in your business the Shingo guiding principles can help your organisation define the ideal behaviour needed to achieve and sustain excellence.

Such ideal behaviour might include:

- safety and awareness management

- following and continually improving standards

- seeking and using data

- converting data into information to compare with the above standards

- teamwork, with respect and humility

- equipment consciousness, ownership, pride

- willingness to learn new skills

- problem solving root cause/ideas for problem elimination/problem prevention

- improvement suggestions

- experiment and testing to enable improvement

- listening to and acting on ideas

- customer awareness

- fastidious cleanliness, workplace organisation

- eagerness to challenge current state performance.

Clearly defining core systems and their constituent processes is a fundamental step in achieving sustainable enterprise excellence.

How can the organisation drive improvement if it does not have a way to tell the team how it is truly performing?

If there is no process to provide the team with the appropriate skills to understand and improve the process, or an environment that encourages good value-adding ideas and communicates them to the wider business, how can the team be expected to engage in continuous improvement activity?

How can the organisation hope to change its culture if the basic tools to allow teams to do their days’ work are not reliable, are broken or missing?

Or when they work in an environment where firefighting is praised and time to fix things and develop standards is not available?

We encourage organisations to look beyond the answers and reflect on the core business systems that should be supporting appropriate behaviour: systems such as the system of improvement, the learning and development system, the system of measurement and management.

Recognising the link between systems and behaviour patterns is all well and good. But if leaders do not have the sensitivity, awareness and ability to encourage and coach appropriate behaviour, or the courage and resilience to deal with inappropriate behaviour when it arises, then all the efforts to link systems to ideal behaviour will be to no effect.

Leaders must adopt a radical change in their management style, from a traditional “command and control” to a “systems thinking” leadership style as illustrated in Figure 4 below (adapted from Seddon, J, Freedom from command and control [1]). This illustrates a fundamental shift in management style via the five main characteristics listed in the centre column. This journey is evolutionary (rather than revolutionary), secured and sustained by a robust evidence-based audit process at each stage.

The role of leader standard work with TPM

As the necessary culture of greater equipment consciousness and equipment performance is built and sustained, leader standard work done well acts as the “sustaining cement”. “Done well” means the LSW is carried out by leaders equipped with effective coaching skills and supports the agreed behavioural norms necessary to sustain this culture. Examples are given by Hines and Butterworth in The Essence of Excellence [2].

Leader standard work is a system that ensures that leaders develop the right culture by undertaking the right activity in the right style by:

- understanding the roles and responsibilities of leaders at all levels

- checking that activity is taking place to ensure business success

- recognising people’s contribution to success

- identifying coaching and development opportunities, so that…

- the whole organisation engages its people with the members taking initiative.

As teams begin to develop consciousness and skills around equipment performance and improvement, the measurement and visualisation of performance trends becomes integrated into daily and weekly visual performance management boards. As equipment is returned to its ideal state, with clear indicators for standard running conditions and surrounding workplace organisation, it makes possible the “visual factory” which can “speak to us” through simple visual cues. All leaders in a business that is reliant on the consistent high performance of its assets must understand how to “read” the visual factory and “listen” to the voice of the process.

Where there is divergence from an agreed standard, it must be addressed immediately with effective and thoughtful inquiry which both allows the situation to be returned to the agreed standard and is followed up by a full inquiry as to the root cause of the divergence. This investigation must be immediate and cannot wait to go through the various channels before the obvious questions are asked.

The consequence of a leadership team’s insensitivity to obvious and intentional signalling systems from the process are fatal to the sustainability of the desired cultural change. If the leader fails to make the observation when he or she is in a situation to make it, this sends many bad signals to the work team such as:

- I always knew our leadership team don’t really get this!

- After all the effort the team put in to creating this visual factory, our leaders are not really tuned into it despite all the noise that was made about it!

To help avoid this situation, a thorough TPM programme will make critical checkpoints clearly visible around the equipment which make it simple to understand the ideal condition of the equipment at that point. An equipment diagram and guide map close to the visual management board can be used to locate these critical control points (see Figure 5). In this way, during a Gemba or shop floor visit the leader will know what to check and where, and can therefore clearly understand what the ideal condition should be. Ideally these checks will form part of daily and weekly supervisor leader standard work and can be included in senior leaders’ standard work as they carry out their regular Gemba walks.

The times when things are difficult or where there is a “fire” are the times when leaders are most tested. In these situations, leaders must be seen to uphold and observe agreed process standards and standards of behaviour. It is at these times that true leadership comes forward and fake leadership is exposed. It is often at these times that senior leaders are chastened and humbled by the leadership shown by front-line teams who are committed to the maintenance of the standards and ways of working that they have developed, and they know are right. It is one of the great rewards of consultancy practice to observe leadership from the bottom up in action.

TPM enables the workplace to “speak to us as leaders”. For leaders, the clear visual indicators enable them to ask the right question and engage in effective enquirer and coaching conversations. In addition, standard walk-around routes for equipment with clear visual standards and point of use instructions enable effective system review as part of LSW. Leaders should ask: Is the asset management system actually working as expected? Is it driving focused improvement and can I see evidence of this? Are we maintaining standards? Are we enabling teamwork?

Conclusion

In the book TPM: a Foundation of Operational Excellence [3], in one of the main case studies pharmaceutical company and Shingo award winner Mylan Rottapharm highlights its approach:

“…the SLT meet with a production and a support team once a week and review the team’s visual management board. Performance metrics and areas that the teams need support are discussed. Each team meets with the SLT at least once a quarter. Both the SLT and middle managers also meet with the people in the company in what are called Gemba Walks. The SLT and middle managers split into small teams and go out and ask people how they are getting on, from both a work and general perspective aimed at engaging with the people in the organisation. These Gemba walks have proven successful in allowing opportunities for improvement to be identified and in some cases explaining why certain policies or procedures are in place. This has helped to create an open and honest culture with people that are also engaged and focused on operational efficiency…”

As authors of the book we are of the firm belief that TPM, considered as a complete system, can enable and sustain the necessary culture and behaviour to drive consistent reliable performance. It also provides the organisation with a framework to truly engage and develop employees in a way that is focused and aligned with core business goals and performance.

[1] Freedom from Command and Control, John Seddon, Vanguard Education 2003. ISBN 0954618300

[2] The Essence of Excellence, Peter Hines and Chris Butterworth. S A Partners, January 2019, £29.99. ISBN 1999374800

[3] TPM – a foundation of operational excellence. Peter Willmott, John Quirke and Andy Brunskill. Published by SA Partners, 2019. ISBN 978-1-9993748-1-5. £39.99 with a £2 donation shared between Friends of Chernobyl’s Children and The Prince’s Trust for each copy sold.