ABSTRACT

It is explained that calculating a Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) as a measure of the reliability of a plant is by no means a straightforward exercise and may be misleading. What constitutes a ‘failure’, and when it should be included in the calculation – and why – must be clearly understood and agreed. Likewise for ‘operating time’, ‘period of observation’ and equipment monitored.

INTRODUCTION

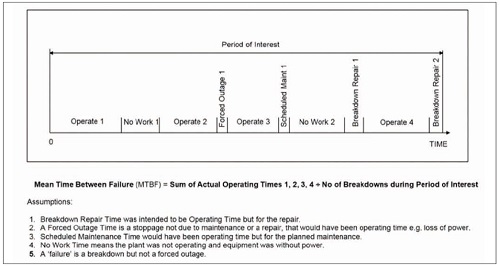

Calculating a Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) is often done to generate an indicator of plant and equipment reliability. An MTBF value is the average time between failures. There are serious dangers with the use of MTBF that need to be addressed when you do this. Take a look at the diagram below representing a period in the life of an imaginary production line. What is the MTBF formula to use for the period of interest to represent the production line’s reliability over that time? If MTBF is the ‘Mean Time Between Failure’, a parameter applying to repairable systems (while MTTF, the ‘Mean Time To Failure’, applies to unrepairable systems) the MTBF formula would need to have time units in the top line and a count of failures on the bottom line.

In the diagram you will see the MTBF formula that I finally settled on, i.e. Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) = Sum of Actual Operating Times 1, 2, 3, 4 divided by Number of Breakdowns during Period of Interest.

But the MTBF value you get from that calculation changes depending on the choices you make. To arrive at an MTBF equation there are assumptions and options to consider. Such as – What event is, ot is not, a ‘failure’? What power-on time do you consider to be equipment operating ‘time’? When do you start and end the period of interest for which you are doing the calculation?

DEFINITION OF FAILURE

To measure MTBF you need to count the failures. But some failures are out of your control and you cannot influence them, like lightning strikes that fry equipment electronics, or floods that cause short circuits, or if your utility provider turns off the power or water supply. Do you include Acts-of-God into your MTBF calculation? In reliability engineering a ‘failure’ is considered to be any unwanted or disappointing performance of the item/system being investigated. That definition leaves ‘failure’ wide-open to interpretation.

Is a ‘failure’ only ever a breakdown? Is a ‘failure’ any time the production line stops no matter what the cause? Is a power black-out caused by the utility provider a ‘failure’ you should count? Is an operator error that stops production but does no other harm a ‘failure’? Should you include all types of failures in your MTBF calculation—that will give you a short MTBF value? Or do you remove certain categories of stoppages when using an MTBF formula — which will give you a longer MTBF value? But which categories do you and don’t you count?

If, in the imaginary production plant time-line modelled above, you included in the MTBF calculation not only the two breakdowns but also ‘Forced Outage 1’ you would get a MTBF one-third lower than if you had only included the two breakdowns. That is a substantial impact on the MTBF value. To make sense of a MTBF calculation you need to know what ‘failures’ are included and which ‘failures’ are not. And you also need to understand why those choices were made.

DEFINITION OF OPERATING TIME

When is an item of plant or equipment operating?

Equipment parts are degraded by the applied stresses put on their atomic structure. The greater the stress suffered, the greater the resulting impact on the item’s operating life. When a vehicle is stopped at red traffic lights the engine is running under the least working load. The gearbox and the rest of the drive train are not in use. When parts are under no stress their atomic structure suffers no harm. When equipment working assemblies are at least stress their parts last longer. For the MTBF calculation of the vehicle do you include its idle times, or just the times it carries sufficiently high working load that causes stress in the parts?

Would you consider the ‘equipment operating time’ for the MTBF calculation as any time it was turned on, or only when it was suffering under working loads? If, in the MTBF formula, you included all operating time from when the vehicle started, and not only when the parts were under working stress, your MTBF value would be higher. But that Mean Time Between Failure value would not be representative of those vehicles that are continually working and hardly ever idling.

You cannot use MTBF as an indicator to compare the same equipment model, assembly number or part number if they are suffering under different working situations.

To make sense of a MTBF calculation you need to know the specific situation and operating scenarios being measured.

Selecting the time period

Because you count ‘failure’ events during a period of time in your MTBF calculation the period of interest selected affects the resulting MTBF value. In the above timeline the period used in the MTBF reliability analysis is through to the end of the second breakdown. If I had chosen to make the time period through to the end of ‘Operate 4’ the second breakdown would not be counted in the MTBF calculation and I would double the MTBF value. By altering the date to exclude one failure event I doubled MTBF—see what magic you can do with MTBF!.

Notice how the two equipment breakdowns are well to the right hand side end of the timeline. Even though the first breakdown happened long into the period of interest, the MTBF for the period does not recognise the dates of those failures. The MTBF was outstanding performance up until the first breakdown, then it dropped, and it dropped again with the second breakdown. A MTBF calculation presumes ‘failures’ are distribute evenly across the period, even though that is not the real historic truth. A MTBF value is hardly ever honest about what actually happened.

To make sense of a MTBF calculation you need to know the time period selected. You also need to know why that duration was used and not some other period.

SELECTING THE EQUIPMENT TO MONITOR

One more issue to consider with regards to MTBF is whether you measure a whole process or measure individual equipment within a process. A complete process suffers MTBF loss every time one of its critical items ‘fails’. If you have a problem piece of plant that brings down the MTBF performance of the whole process, the ‘bad actor’ needs to be flagged as the performance destroying cause.

The companies who take the whole line/process into MTBF calculations often struggle to get a high MTBF due to ‘bad actors’ failing within the system being monitored. Those companies also need to measure individual equipment MTBF to identify the problem plant so its failure causes can be addressed and the ‘bad actor’ made more reliable.

HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF FROM THE MTBF CALCULATION TRAP

MTBF calculations are a statistical trap easily fallen into. A MTBF value can be a total fabrication. Some managers remove or add all kinds of MTBF parameters to make their department look good (like not counting ‘failures’, changing period lengths, and the like). But that is a falsehood. I once came across a company that did not count stoppages less than 8 hours duration in their MTBF calculation. They weren’t ‘breakdowns’ but they were forced outages over which they had full control. What a joke I thought. What an absolute rubbish way to run a business. You can never improve a company if people tell lies about its performance and hide the truth of where the troubles lay.

You need to get agreement across the company as to what can be called a ‘failure’, what can be called ‘operating time’ and what are the end points of the time period being analysed before you can use MTBF values as a believable Production Reliability KPI (Key Performance Indicator).

Maybe it is more sensible to have MTBF by categories, e.g. 1) mean time between machinery/equipment breakdowns caused by internal events, 2) mean time between operator induced stoppages, 3) mean time between externally caused outages that you cannot control, like power or water loss, and so on.

Your second best protection against misinterpreting and misunderstanding MTBF is to have honest, rigid rules covering the choices and options that arise when doing a MTBF calculation.

The very best protection is to also get the timeline of the period being analysed showing all the events (and their explanations) that happened, and then ask a lot of questions about the assumptions and decisions that were made, and not made, to arrive at those MTBF values.

Mike Sondalini is the author of Industrial and Manufacturing Wellness, The Complete Guide to Successful Enterprise Asset Management (2nd Ed. 2016). Industrial Press Inc. Available in hardcover or Kindle from Amazon.

Mike Sondalini is the author of Industrial and Manufacturing Wellness, The Complete Guide to Successful Enterprise Asset Management (2nd Ed. 2016). Industrial Press Inc. Available in hardcover or Kindle from Amazon.